Examining Physiological Effects of Repeated Weight Cycling

Educational content only. No promises of outcomes.

Educational content only. No promises of outcomes.

During periods of severe calorie restriction, the body exhibits adaptive thermogenesis—a reduction in resting metabolic rate that exceeds what would be expected based on changes in lean body mass alone. This down-regulation of energy expenditure occurs as part of metabolic adaptation to prolonged energy deficit.

Research indicates that the hypothalamus and sympathetic nervous system coordinate this response, reducing thyroid hormone production and increasing metabolic efficiency. This adaptation serves a protective function during extended energy deficit but contributes to altered metabolic dynamics when refeeding occurs. The degree of adaptation varies between individuals and across repeated cycles.

Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT)—the energy expended through occupational and spontaneous physical activity—undergoes disproportionate reduction during weight loss phases. This suppression occurs alongside conscious changes in structured exercise and is mediated by alterations in dopaminergic signalling and motivational pathways.

Studies in metabolic chambers have documented reductions in NEAT of 20–30% during caloric restriction, attributable to both reduced fidgeting, occupational movement, and postural changes. This unconscious energy conservation mechanism can partially persist during refeeding phases, contributing to the metabolic challenges of repeated cycling.

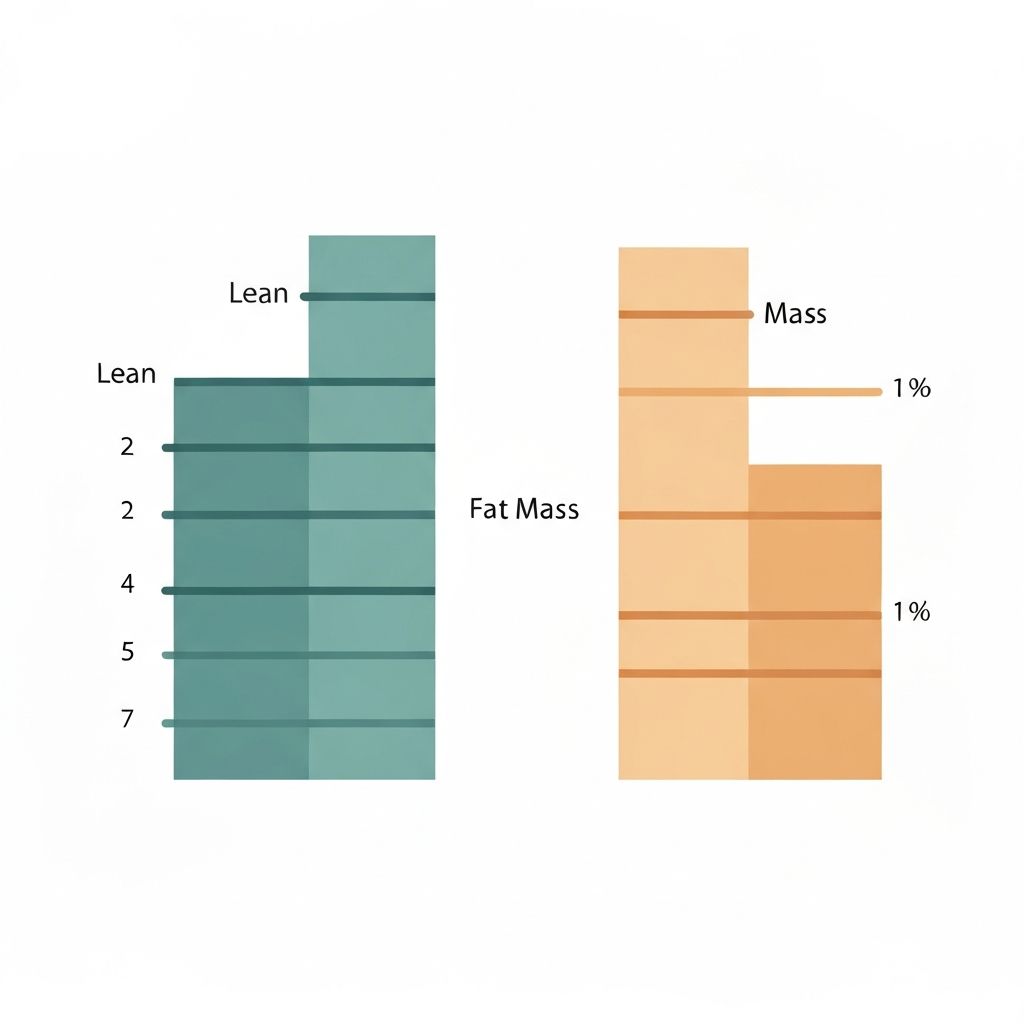

Following periods of caloric restriction, the refeeding phase is characterised by preferential regain of fat mass relative to lean tissue recovery. This pattern emerges because metabolic efficiency remains elevated, and the body prioritises restoration of energy reserves in the form of adipose tissue.

Animal and human weight-cycling studies demonstrate that fat regain typically accounts for 60–80% of the refeeding phase weight, whilst lean mass recovery lags considerably. This imbalance becomes more pronounced with repeated cycles and is linked to sustained elevations in appetite hormones, particularly ghrelin, and altered leptin signalling patterns.

Repeated cycles of severe restriction and refeeding demonstrate effects on mitochondrial efficiency and substrate oxidation capacity. Animal models show alterations in electron transport chain function and reduced oxidative phosphorylation efficiency following multiple weight cycles.

These mitochondrial adaptations are thought to reflect long-term metabolic reprogramming in response to repeated energy stress. Changes in mitochondrial biogenesis markers and enzymatic activity suggest that cumulative cycling may alter cellular energy production efficiency, though the functional consequences in human populations remain an active area of investigation.

Weight cycling produces lasting changes in leptin signalling and hypothalamic appetite regulation. During restriction, leptin levels drop acutely, triggering compensatory increases in hunger hormones. Following refeeding and weight regain, leptin restoration may be delayed or incomplete.

Repeated cycling appears to blunt leptin's appetite-suppressing effects, a phenomenon termed leptin resistance. This altered signalling contributes to elevated baseline hunger in individuals with a history of multiple weight loss and regain episodes. Additionally, disturbances in other appetite-regulating peptides such as peptide YY and GLP-1 have been documented in weight-cycling models.

Weight-cycling protocols in both animal and human studies reveal increases in fasting insulin levels and indices of insulin resistance. These changes are particularly pronounced when fat regain occurs in excess of lean mass recovery, creating a metabolic profile characterised by central adiposity and ectopic lipid accumulation.

Intramuscular triglycerides and hepatic lipid content increase during refeeding phases following restriction, particularly in repeated cycling scenarios. This pattern is thought to reflect the combined effects of elevated metabolic efficiency, preferential fat regain, and impaired insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in previously restricted tissues. The long-term trajectory of these markers across multiple cycles remains an important research question.

Beyond metabolic adaptations, repeated cycles of restriction and refeeding create behavioural reinforcement patterns. The acute psychological relief and reward-circuit activation associated with food availability following restriction may strengthen restriction–binge cycle patterns through dopaminergic learning mechanisms.

This neurobiological reinforcement can promote recurrent engagement in restrictive eating patterns, independent of conscious intention. Understanding the interplay between metabolic adaptation and conditioned behavioural responses is important for recognising the complexity of weight-cycling physiology and the multifactorial nature of sustained dietary adherence challenges.

| Study Type | Key Observations | Metabolic Marker | Notable Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Ward Studies | Controlled restriction & refeeding cycles | Resting Energy Expenditure | 10–15% reduction beyond expected lean mass loss |

| Animal Weight-Cycling Models | Multiple restriction–refeeding cycles | Mitochondrial Efficiency | Reduced oxidative phosphorylation; altered substrate oxidation |

| Long-Term Cohort Data | Individuals with repeated dieting history | Insulin & Leptin Levels | Elevated fasting insulin; blunted leptin signalling |

| Body Composition Analyses | Fat vs lean regain patterns | Fat Mass Recovery | 60–80% of weight regain as fat tissue |

| NEAT Assessments | Activity monitoring during cycling | Non-Exercise Thermogenesis | 20–30% suppression during restriction phases |

| Meta-Analyses | Systematic review of cycling studies | Weight Variability Outcomes | Metabolic heterogeneity; individual response variation |

The physiological consequences of weight cycling are not uniform across all individuals. Genetic factors, prior dieting history, baseline metabolic health, and age all influence the magnitude and persistence of metabolic adaptations. Some individuals demonstrate substantial suppression of energy expenditure during restriction, whilst others show more modest changes.

Similarly, the degree of preferential fat regain and the duration of leptin signalling disturbances vary considerably between individuals. This heterogeneity highlights the importance of recognising individual variation in weight-cycling physiology and the limitations of generalising population-level findings to specific individuals.

Explore the mechanisms of metabolic adaptation, including sympathetic nervous system changes and thyroid hormone dynamics during extended restriction phases.

Read detailed explanation →Understand how NEAT suppression occurs during dieting and the role of dopaminergic pathways in reduced spontaneous physical activity.

Read detailed explanation →Learn why refeeding phases result in preferential fat mass recovery and the hormonal factors driving this metabolic outcome.

Read detailed explanation →Discover research findings on how repeated cycles affect mitochondrial function, oxidative capacity, and substrate utilisation.

Read detailed explanation →Examine changes in appetite regulation hormones, including leptin resistance patterns and their persistence across multiple cycles.

Read detailed explanation →Review the genetic, physiological and environmental factors influencing individual differences in weight-cycling responses.

Read detailed explanation →

Weight cycling refers to repeated cycles of weight loss followed by weight regain, often referred to colloquially as "yo-yo dieting." Unlike intentional, sustained weight loss, which typically involves reaching a target weight and maintaining it, weight cycling is characterised by oscillation—losing weight, regaining it, and then repeating the cycle. The physiological consequences arise from the repeated exposure to restriction and refeeding, not from the simple fact of carrying extra weight.

Adaptive thermogenesis is an evolutionary survival mechanism. During periods of food scarcity, reducing metabolic rate preserves energy stores and increases survival likelihood. This occurs through coordinated changes in thyroid hormone production, sympathetic nervous system activity, and changes in metabolic enzyme expression. In modern contexts, this mechanism persists despite intentional caloric restriction and contributes to the difficulty of sustained weight loss.

The evidence indicates that metabolic adaptations from weight cycling are substantial and can persist long-term, but the term "permanent damage" mischaracterises the physiology. Adaptations can be partially reversed through sustained energy balance and regular physical activity. However, recovery may be incomplete and slower than the initial adaptive response. Individual variability is significant, and some individuals show more persistent changes than others.

Leptin, an appetite-suppressing hormone produced by adipose tissue, drops sharply during caloric restriction, triggering compensatory increases in hunger hormones. During refeeding and weight regain, leptin levels typically restore, but repeated cycling can blunt leptin's appetite-suppressing effects—a condition termed leptin resistance. This altered signalling contributes to sustained elevated hunger in individuals with a cycling history.

Yes. Research suggests that the metabolic impact of repeated cycling accumulates. Earlier cycles may produce modest metabolic adaptations, whilst subsequent cycles often show more pronounced changes in energy expenditure, fat regain patterns, and appetite hormone alterations. This cumulative effect highlights the progressive nature of physiological changes with repeated exposures to restriction–refeeding cycles.

Metabolic adaptations from weight cycling show partial reversibility. Sustained energy balance, regular physical activity, and adequate micronutrient intake can gradually restore more typical metabolic patterns. However, complete reversal may not occur, particularly following multiple cycles, and the timeline for recovery can be prolonged. Individual factors such as age, genetics, and baseline metabolic health influence the degree of reversibility.

During refeeding, elevated metabolic efficiency and the rapid restoration of depleted energy reserves favour fat accumulation over lean tissue synthesis. Muscle protein synthesis requires sustained positive protein balance and mechanical stimulation, which may be suboptimal during rapid refeeding if protein intake is inadequate or structured exercise is insufficient. Additionally, hormonal changes favour anabolic signalling in adipose tissue relative to skeletal muscle.

Regular resistance and aerobic exercise can attenuate some metabolic adaptations during restriction and may favour greater lean mass preservation and recovery during refeeding. However, exercise alone cannot completely prevent the physiological shifts associated with severe caloric restriction. The combination of adequate protein intake, resistance training, and moderation of deficit magnitude appears more effective than any single intervention.

Rapid weight loss typically produces more pronounced metabolic adaptation than gradual loss, particularly greater reductions in NEAT and resting energy expenditure. Rapid regain following rapid loss also tends to result in higher fat:lean mass ratios during refeeding. Slower weight loss and more modest deficits may reduce the magnitude of adaptive responses, though the cumulative effects of repeated cycles still influence outcomes substantially.

Weight cycling, particularly when followed by preferential fat regain and central adiposity accumulation, is associated with increased fasting insulin levels and reduced insulin sensitivity. Repeated cycles amplify these insulin resistance markers. Ectopic lipid deposition (fat in muscle and liver) during refeeding phases further impairs insulin-stimulated glucose uptake, creating a metabolic profile characteristic of metabolic syndrome.

The timeline varies significantly between individuals. Some metabolic markers (such as energy expenditure elevation) may partially recover within weeks to months of achieving stable weight. However, alterations in appetite hormone signalling and mitochondrial efficiency can persist for years. The duration of persistence appears to increase with the number of previous cycles, and complete normalisation may not occur following multiple episodes.

Genetic predisposition (estimated heritability ~40–60% for metabolic response variation), older age, prior dieting history, and baseline metabolic dysfunction all predict greater susceptibility to weight-cycling effects. Individuals with higher baseline leptin resistance or lower baseline mitochondrial efficiency may also show more pronounced adaptive responses. Sex hormones may also influence cycling responses, though research is ongoing.

Discover detailed research-referenced information on the physiological mechanisms of repeated weight cycling and individual metabolic variability.

Explore Our Articles